In this article, we examine trends in overland flood insurance take-up across Canada based on the 2021 CatIQ exposure data release. Flood-related events have caused over $5.5 billion in insured losses in Canada from 2012-2021. With climate change, losses to flood in Canada are expected to increase. Flood insurance can be an important tool to finance these losses if it is adopted widely across Canada. While overland flood insurance coverage for personal homes was introduced in Canada in 2015, its addition as a rider to insurance policies is optional and take-up varies dramatically across the country and over time.

We track personal flood insurance take-up in CatIQ data as a fraction of personal fire insurance take-up. In Canada, flood insurance exists as an additional endorsement to a homeowner’s or tenant’s insurance policy. We consider take-up both by number of policies (dividing number of flood insurance policies by fire insurance policies) and by value of insured property (dividing sum of buildings and contents covered by flood insurance policies by the same for fire insurance policies). These numbers tend to be similar; when take-up by the value of policies exceeds take-up by number of policies, it suggests more valuable assets are more likely to be insured for flood. Please note this metric should not be interpreted as the overall penetration of flood insurance in a region since not all homeowners and tenants have insurance.

Flood insurance take-up rates have grown steadily over time in Canada. In 2016, the first year of data available in CatIQ and one year following its introduction, flood insurance take-up rates were roughly 25% of that of fire insurance. Flood insurance take-up grew steadily to just under 40% by 2018. In 2021, the latest data release, roughly 55% of personal insurance policies have flood insurance. However, flood insurance take-up is still low across many parts of the country. Tables 1 and 2 show the personal flood insurance take-up rates as a fraction of fire insurance by number of policies and by value, respectively, across the provinces of Canada. There is significant variation in flood insurance take-up rates across the provinces. Manitoba had the lowest flood insurance take-up rates in Canada, with the next-lowest province having almost double the flood insurance take-up rates. By contrast, Alberta, British Columbia, Nova Scotia, Ontario, and Quebec had over half of personal lines with flood insurance coverage in 2021.

Table 1. Flood insurance take-up as fraction of fire insurance, by number of policies

| CAN | AB | BC | MB | NB | NL | NS | ON | PE | QC | SK | |

| 2018 | 38% | 27% | 39% | 11% | 28% | 26% | 27% | 40% | 17% | 45% | 31% |

| 2021 | 54% | 53% | 55% | 20% | 42% | 38% | 54% | 57% | 37% | 57% | 42% |

Table 2. Flood insurance take-up as fraction of fire insurance, by value insured

| CAN | AB | BC | MB | NB | NL | NS | ON | PE | QC | SK | |

| 2018 | 39% | 30% | 45% | 10% | 31% | 32% | 31% | 42% | 21% | 42% | 30% |

| 2021 | 55% | 59% | 53% | 19% | 41% | 46% | 54% | 58% | 38% | 58% | 41% |

The territories of Northwest Territories, Nunavut, and Yukon have flood insurance take-up rates very similar to those of the rest of Canada in 2021. As a fraction of total values insured, they were 43%, 58%, and 43% respectively. The rate of growth of flood insurance take-up over the past 3 years was much higher in the territories. Flood insurance take-up averaged below 5% of fire insurance take-up in the territories in 2018.

Flood take-up rates within provinces vary dramatically across Forward Sortation Areas (FSAs), or 3-digit postal codes. Generally, flood insurance take-up rates were higher in metropolitan FSAs compared to rural FSAs. In the denser metropolitan FSAs, flood insurance take-up rates often exceed 70% of the fire insurance take-up rates. Some FSAs even see 80% or 90% take-up of flood insurance. In contrast, rural FSAs rarely exceed 60% take-up of flood insurance even in provinces with higher take-up rates.

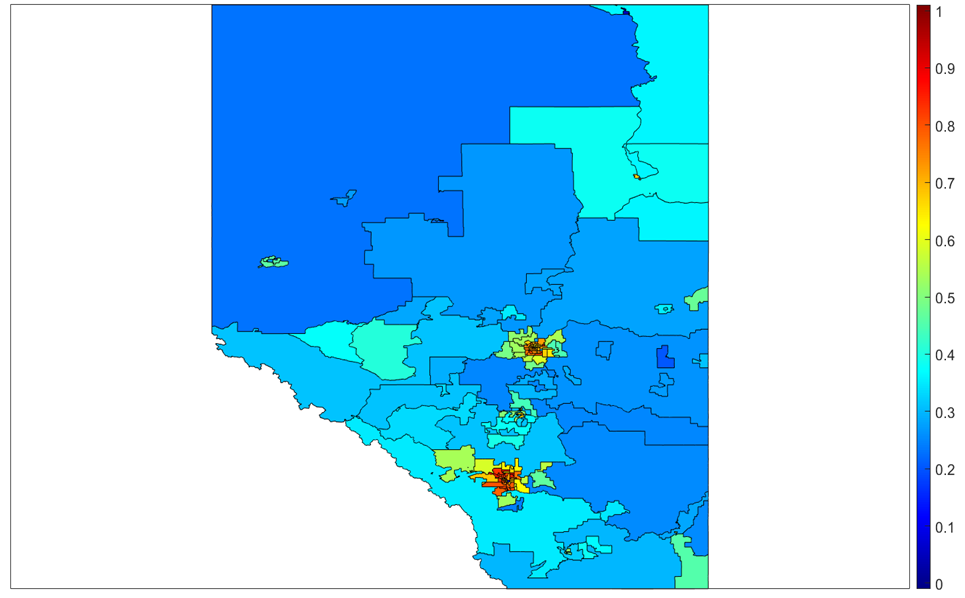

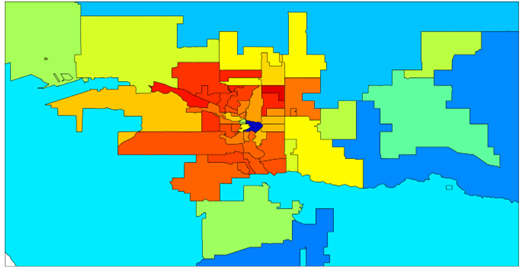

Figure 1 maps Alberta’s flood insurance take-up by FSA, along with a zoomed-in look at the denser Calgary and Edmonton metropolitan areas (an unfortunate limitation of these maps is more populated FSAs tend to be smaller than less populated FSAs, so the size of an FSA does not represent its importance). Alberta follows the general pattern of lower flood take-up in rural FSAs and higher flood take-up in urban FSAs more starkly than most provinces. Flood insurance take-up rates are high in Edmonton and even higher in Calgary, with some FSAs nearing or exceeding 90% take-up. Outside of these urban areas, few other FSAs exceed 40% take-up of flood insurance.

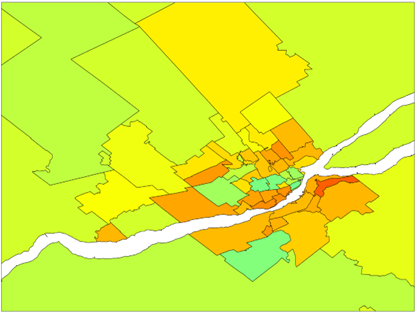

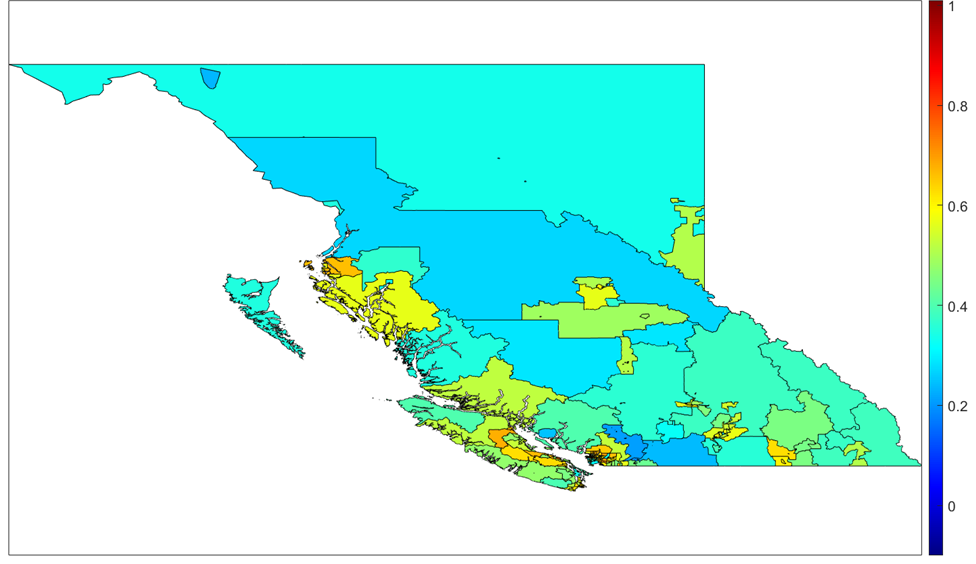

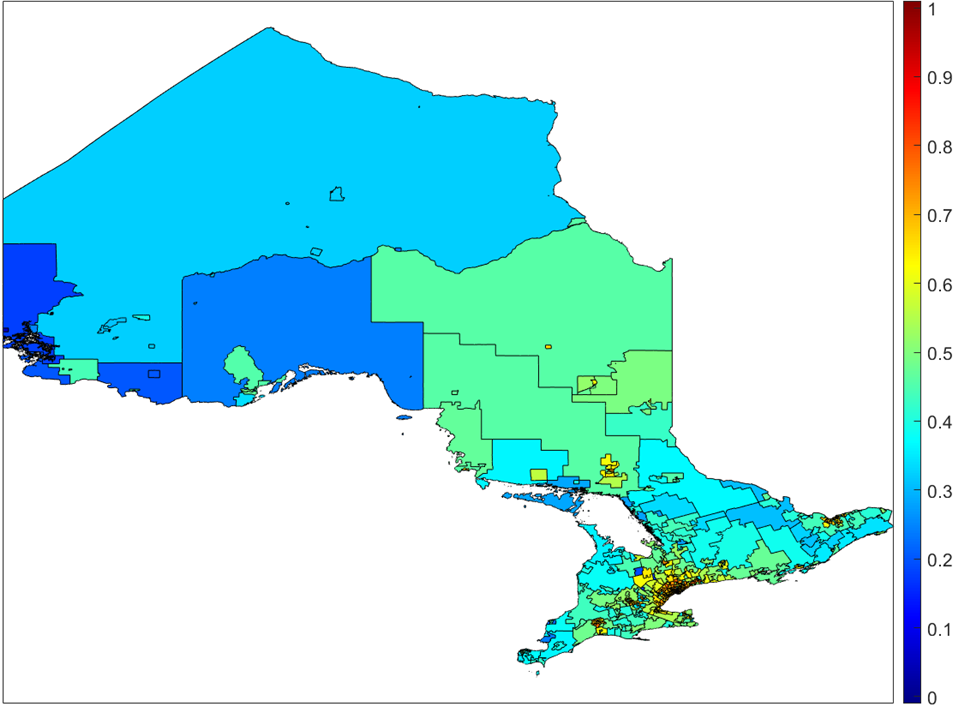

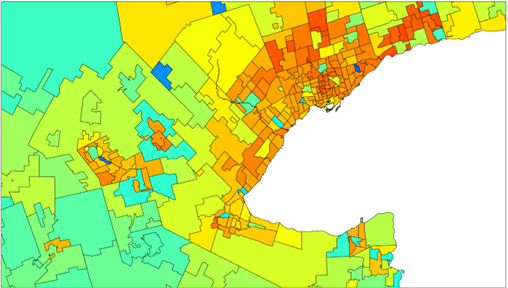

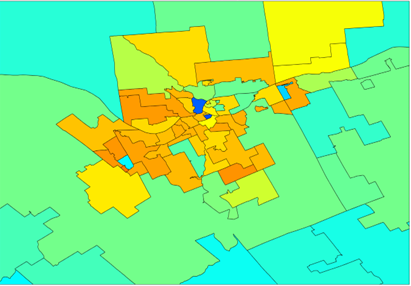

Ontario follows a similar pattern as Alberta (see Figure 3), although not quite as extreme. Rural FSAs tend to have lower take-up rates, but unlike Alberta, there are several rural Ontario FSAs with take-up in the 50% range. Ontario’s urban flood insurance take-up rate is still relatively high. Most of these FSAs are in the 60%-80% range, compared to Alberta’s 70%-90%.

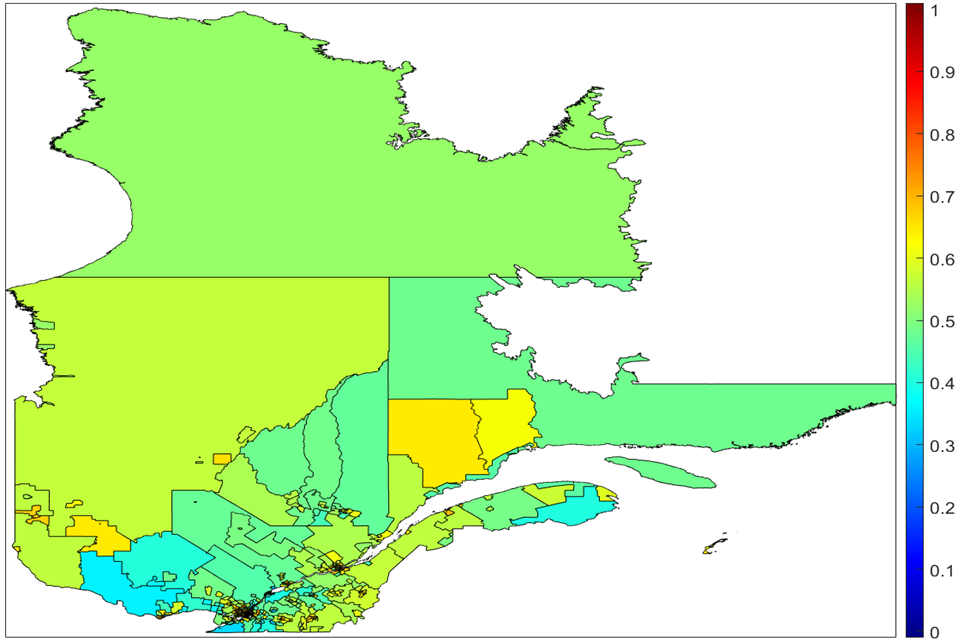

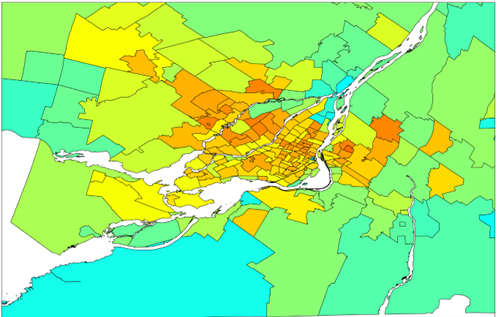

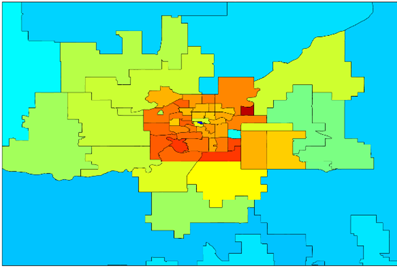

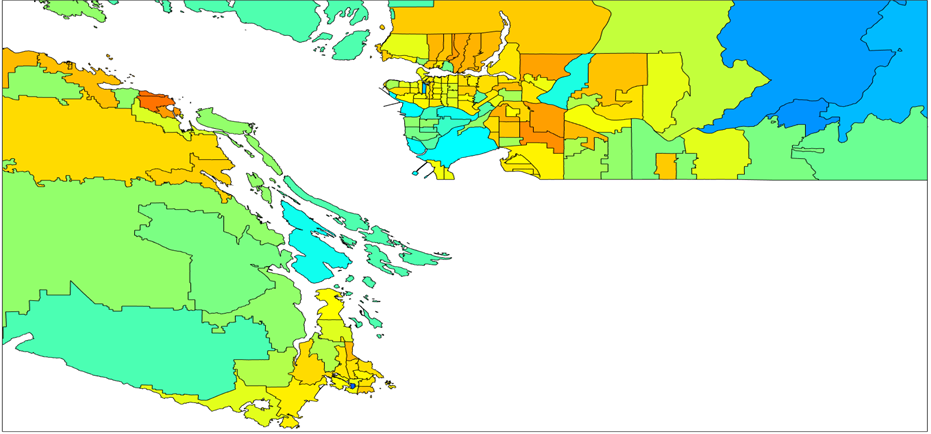

By contrast, British Columbia and Quebec has a more even spread of flood insurance take-up rates across FSAs (see Figure 2 and Figure 4). Urban FSAs in these two provinces still tend to have higher flood insurance take-up compared to rural FSAs, usually around 70%. Notably, the Richmond and Delta FSAs have relatively low take-up rates compared to other urban areas, and even Vancouver FSAs tend to have take-up rates in the 60%-70% range. On the other hand, B.C.’s rural FSAs tend to have relatively high take-up rates, with most in the 40%-60% range. Quebec’s rural FSAs have even higher take-up rates on average with take-up almost never dropping below 40%.

The growth in the take-up rate of flood insurance from 2018 to 2021 has also been highly uneven across Canada. Calgary, Edmonton, and Toronto were among regions that grew the most, with many of these FSAs growing around 30 percentage points. Some provinces, such as Alberta and Quebec, grew relatively evenly across the entire province. Other provinces, including British Columbia and Ontario, had mixed growth with some FSAs having almost no growth in the take-up of flood insurance. As FSAs with easier growth opportunities approach universal take-up of flood insurance, it may be interesting to examine how provinces like Alberta and Quebec have sustained broad-based growth in flood insurance take-up and consider whether these approaches can be effective in other provinces.

Figure 1: Alberta (top), Calgary (middle), and Edmonton (bottom) flood insurance take-up as fraction of fire, 2021, by value insured. Source: CatIQ/ICLR

Figure 2: British Columbia (top), and Vancouver/Victoria region (bottom) flood insurance take-up as fraction of fire, 2021, by value insured. Source: CatIQ/ICLR

Figure 3: Ontario (top), Toronto (middle), and Ottawa/Gatineau (bottom) flood insurance take-up as fraction of fire, 2021, by value insured. Source: CatIQ/ICLR

Figure 4: Quebec (top), Montreal (middle), and Quebec City (bottom) flood insurance take-up as fraction of fire, 2021, by value insured. Source: CatIQ and ICLR.