In the fall of 1922, the city of Toronto sent 85 surplus streetcars to Haileybury and other northern Ontario towns to help house thousands of desperate people who had lost their homes to wildfires.

Known as the Great Fire, it burned nearly 1,700 square kilometres of the area — including the town of Haileybury. It killed 43 people and caused millions of dollars in property damage in 18 townships. A newspaper referred to it as the “worst disaster that had ever overtaken northern Ontario.”

It was not.

The wildfires back then were as fierce, deadly and eerily similar to the ones we have today. And we have yet to learn to live with them.

Fires of the past

The Great Miramichi fire, which destroyed forests and devastated communities across northern New Brunswick in 1825, was the largest and one of the most deadly wildfires in North American history.

The Saguenay and Ottawa Valley fires in 1870 could have been just as deadly when they forced the evacuations of several thousand people. The capital city would have burned down that summer had it not been for a quick-thinking engineer who ordered the gates of the St. Louis dam on the Rideau Canal to be breached so that it would flood city streets.

Seventeen villages were levelled in Wisconsin the following year, killing between 1,200 and 1,500 people.

In 1881, the Michigan’s Thumb fires burned 1,480 barns, 1,521 houses and 51 schools, while killing 283 people and injuring many others. Smoke from those fires coloured the sky over Toronto.

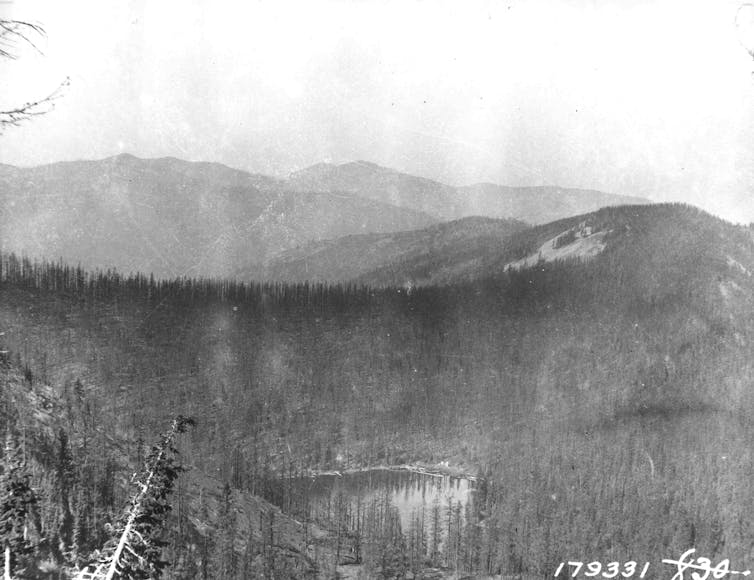

In 1908, the British Columbia town of Fernie was levelled by a wildfire. In 1911, the Porcupine fire killed 73 people while levelling the towns of South Porcupine and Pottsville in Ontario before partially destroying Golden City and Porquis Junction.

There was almost no warning five years later when a deadlier complex of fires swept through the same region and killed 223 people.

Each summer and fall, it seemed, ended badly somewhere.

Déjà vu

The similarities between the fires now and then are uncanny, as described in my book Dark Days At Noon: The Future of Fire. The ignition of fires between 1870 and 1922 was fuelled by higher temperatures, drier forests and the kind of elevated lightning activity that we are experiencing today.

Much of the warming back then can be attributed to the end of the little ice age (1300 to 1850) that dramatically cooled parts of the world, and the Industrial Revolution in the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

Today, the unprecedented warming taking place is primarily because of the burning of fossil fuels.

Forest land-grabbing and negligence has also fuelled numerous fires in the past and present.

Before and beyond the turn of the 19th century, people moved into boreal and temperate forests to take advantage of cheap land and jobs in the mining and forestry sectors. Today, people are building luxurious country homes in places like the Okanagan to escape the cost of living in big cities.

Sparks from trains and the careless disposal of locomotive ash accounted for a significant number of fires in Ontario in the past. Following the Lytton fire in B.C. in 2021, the head of Canada’s Transportation Safety Board acknowledged that more work is still needed to prevent wildfires caused by trains.

Gaps in public policy

The other thing that hasn’t changed much is public policy. The Porcupine fire in 1911 as Canada’s version of the Big Burn, a complex of fires that swept through the northern Rockies of the United States in 1910 and resulted in sweeping policy changes.

Following the Big Burn, the U.S. passed the Weeks Act that authorized the government to purchase up to 30 million hectares of land to protect watersheds from development and wildfire. This mandated the U.S. Forest Service to work with state fire bureaus, which were happy to co-operate because it came with funding they could not otherwise afford.

In contrast, Canadian politicians failed to do what was necessary to prevent future fires. The government, which owned many of the railroad companies, blamed Indigenous people for many fires. Better legislation and fire management strategies were still not in place five years after the Porcupine fire when the Matheson fire took the lives of 223 people. Nor were they there in 1922, when the Great Fire devastated Haileybury.

Canada had a chance to replicate what the U.S. Forest Service was doing, but failed to as funding for fire research and management was badly decimated by budget cuts and the off-loading of responsibilities to the provinces in the 1930s.

Even today, provinces like Alberta have cut wildfire budgets to save money, only to pay the price when wildfires like the 2016 Fort McMurray wildfire, which forced the evacuation of 88,000 people.

Managing future fires

The fact that fire is still entering towns like Lytton and Fort McMurray without adequate warning suggests we have yet to learn to live with the fires that we have stoked by burning fossil fuels, draining wetlands and suppressing natural fires that would have otherwise produced more resilient forests.

Stopping Indigenous burning that aided forest regeneration didn’t help.

We are now in a unique situation where hot fires are creating their own weather — fire-driven thunderstorms and pyrogenetic tornadoes — that can spawn other fires. We saw this in Fort McMurray in 2016, in B.C. in the following years and in 2019 and 2020 when Australia’s Black Summer fire season led to a massive outbreak of fire-induced and smoke-infused thunderstorms.

This is, in a word, scary.

The title of my book Dark Days at Noon harkens back to 1780 when smoke from distant fires blocked out so much sunlight that people from all over New England thought the end of the world was at hand. The end of the world is not at hand, but there will be many more dark days at noon if we do not learn to live with fire.

Edward Struzik, Fellow, Queen’s Institute for Energy and Environmental Policy, School of Policy Studies, Queen’s University, Ontario

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.